Behavior Modification

Gamification uses behavior modification to change a person's behavior. Behavior modification focuses only on behavior, not on knowledge or understanding. It views the mind as a black box which a stimulus goes into and a response comes out of, and learning is just getting a person to provide the right response. This is based on behavioral learning theory as described by psychologists like B. F. Skinner. Skinner developed the concept of operant conditioning, in which a system of reinforcements or punishments that came after a specific behavior either increased or decreased the likelihood of that behavior reoccurring in the future.Reinforcements and Punishments

In general, reinforcement is more effective than punishment in making long-term behavior changes. A reinforcement, by definition, increases the likelihood of a behavior reoccurring in the future. A friend of mine used the reinforcement of mini Tootsie Rolls to potty train his son; every time the boy pooped in the toilet, he got a mini Tootsie Roll.

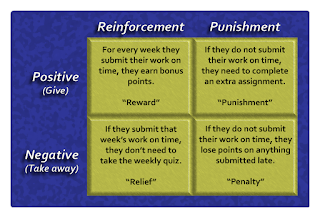

In general, reinforcement is more effective than punishment in making long-term behavior changes. A reinforcement, by definition, increases the likelihood of a behavior reoccurring in the future. A friend of mine used the reinforcement of mini Tootsie Rolls to potty train his son; every time the boy pooped in the toilet, he got a mini Tootsie Roll.There are two types of reinforcements, positive and negative. A positive reinforcement is like a reward, where you are given something you desire in order to behave that way again. The candy was a positive reinforcement, because it was something the boy was given to increase the likelihood that he would poop in the toilet in the future.

A negative reinforcement is also an incentive, but in this case it involves taking something undesirable away. Think of negative reinforcement as relief from something you don't like. In college, my general psychology professor gave a quiz every Friday in this 8:00 class. In order to get us to read the textbook (a behavior), he said anyone who had an A average at the end of the semester wouldn't need to take the final (a relief from the exam). The quizzes covered content in the textbook while the final covered the lecture. So I studied the textbook every week and got an A on every quiz, which meant I could skip the final exam (and every Monday and Wednesday class, but that's another story...).

Punishment, on the other hand, is designed to reduce the likelihood that a behavior is repeated. A punishment or a penalty is given after undesirable behavior to discourage that behavior. One of the problems, though, is making sure the punishment is more odious than giving up the behavior you are trying to discourage.

Punishment comes in positive and negative flavors, too, but they are even harder to understand than positive or negative reinforcement. A positive punishment (which sounds like an oxymoron) is giving something the person doesn't want after the undesirable behavior, like making a child sit in the corner after misbehaving, Negative punishment is like a penalty, where you take away something they do want, like taking away a child's Xbox after they don't do what you tell them to do.

Let's apply these to a behavior you might want to encourage in your class - submitting work on time. Positive reinforcement would be giving students bonus points for turning work in on time (giving something desirable). Negative reinforcement would be dropping their lowest grade (taking away something undesirable) if they submit all of their work on time. Positive punishment would be giving a harder or longer assignment (giving something undesirable) is they fail to submit as assignment on time, while negative punishment would be taking points off or just not accepting late work (taking away something desirable).

For a variety of reasons, reinforcement is almost always more effective than punishment. The simplest reason is when you punish bad behavior, the person still doesn't know what the desirable behavior is, but when you reinforce that desirable behavior, they automatically know what it is they are supposed to do. Punish a child for pooping in their diaper instead of in the potty, and they still don't understand where they are supposed to poop. People are also generally willing to work harder to earn something than they are to avoid losing something in the future. That's why in gamification, reinforcement is used for behavior modification instead of punishment. You earn points for buying coffee but you don't lose points for not buying any.

One challenge in using reinforcement in behavior modification is to make sure the reinforcement given, whether positive or negative, is sufficiently enticing to make people want to change their behavior. It is hard to change behavior, particularly when that behavior is something the person doesn't want to do, or that prevents the person from doing something they do want to do. Another challenge is trying to reinforce the desired behavior every time it occurs. That's called continuous reinforcement, and when you do that, you find the reinforcement become less effective the more you use it. That's why we use a schedule of reinforcement instead.

One challenge in using reinforcement in behavior modification is to make sure the reinforcement given, whether positive or negative, is sufficiently enticing to make people want to change their behavior. It is hard to change behavior, particularly when that behavior is something the person doesn't want to do, or that prevents the person from doing something they do want to do. Another challenge is trying to reinforce the desired behavior every time it occurs. That's called continuous reinforcement, and when you do that, you find the reinforcement become less effective the more you use it. That's why we use a schedule of reinforcement instead.

Punishment comes in positive and negative flavors, too, but they are even harder to understand than positive or negative reinforcement. A positive punishment (which sounds like an oxymoron) is giving something the person doesn't want after the undesirable behavior, like making a child sit in the corner after misbehaving, Negative punishment is like a penalty, where you take away something they do want, like taking away a child's Xbox after they don't do what you tell them to do.

Let's apply these to a behavior you might want to encourage in your class - submitting work on time. Positive reinforcement would be giving students bonus points for turning work in on time (giving something desirable). Negative reinforcement would be dropping their lowest grade (taking away something undesirable) if they submit all of their work on time. Positive punishment would be giving a harder or longer assignment (giving something undesirable) is they fail to submit as assignment on time, while negative punishment would be taking points off or just not accepting late work (taking away something desirable).

For a variety of reasons, reinforcement is almost always more effective than punishment. The simplest reason is when you punish bad behavior, the person still doesn't know what the desirable behavior is, but when you reinforce that desirable behavior, they automatically know what it is they are supposed to do. Punish a child for pooping in their diaper instead of in the potty, and they still don't understand where they are supposed to poop. People are also generally willing to work harder to earn something than they are to avoid losing something in the future. That's why in gamification, reinforcement is used for behavior modification instead of punishment. You earn points for buying coffee but you don't lose points for not buying any.

One challenge in using reinforcement in behavior modification is to make sure the reinforcement given, whether positive or negative, is sufficiently enticing to make people want to change their behavior. It is hard to change behavior, particularly when that behavior is something the person doesn't want to do, or that prevents the person from doing something they do want to do. Another challenge is trying to reinforce the desired behavior every time it occurs. That's called continuous reinforcement, and when you do that, you find the reinforcement become less effective the more you use it. That's why we use a schedule of reinforcement instead.

One challenge in using reinforcement in behavior modification is to make sure the reinforcement given, whether positive or negative, is sufficiently enticing to make people want to change their behavior. It is hard to change behavior, particularly when that behavior is something the person doesn't want to do, or that prevents the person from doing something they do want to do. Another challenge is trying to reinforce the desired behavior every time it occurs. That's called continuous reinforcement, and when you do that, you find the reinforcement become less effective the more you use it. That's why we use a schedule of reinforcement instead.Schedules of Reinforcement

When you use schedules of reinforcement, you don't reinforce the behavior every time, but rather you reinforce after a certain number of behaviors (a rate or ratio schedule) or after a certain time period of exhibiting the behavior (an interval schedule).Ratio Schedules

A fixed ratio schedule results in a reinforcement after a specific number of behaviors. Getting a free cup of coffee after buying four cups of coffee is a fixed ratio. On a fixed ratio schedule, the person's rate of exhibiting the behavior increases the closer they get to the reward - once they buy three cups of coffee, they tend to buy the fourth more quickly to get the reward. Fixed ratio schedules result in a fairly high rate of behavior on average, because they have a known outcome, and the outcome relies on what the person does, but that rate is unsteady and increases the closer they get to the reward. However, if you stop giving the reward, the behavior quickly stops.Interval Schedules

A fixed interval schedule relies on giving reinforcement after a certain time period, rather than after a certain number of behaviors, as long as the behavior occurs in that interval. In the classroom, exams are generally on a fixed interval, because they usually occur after a fixed amount of time. Students tend to increase their study time right before the exam in order to get the reward of a good grade, and then their studying slacks off until the next exam comes around, when it increases again. As long as they study enough (and appropriately) within that time period, they will get the reinforcement of a good grade, and it doesn't matter if that studying is spread out over the entire time interval or all occurs at the end.

A fixed interval schedule relies on giving reinforcement after a certain time period, rather than after a certain number of behaviors, as long as the behavior occurs in that interval. In the classroom, exams are generally on a fixed interval, because they usually occur after a fixed amount of time. Students tend to increase their study time right before the exam in order to get the reward of a good grade, and then their studying slacks off until the next exam comes around, when it increases again. As long as they study enough (and appropriately) within that time period, they will get the reinforcement of a good grade, and it doesn't matter if that studying is spread out over the entire time interval or all occurs at the end.Finally, a variable ratio interval as the reinforcement coming after a random time period. If exams are examples of fixed intervals, pop quizzes are examples of variable intervals. Again, they can occur at any time, or at variable intervals. Just as a a variable ratio schedule results in a steadier rate of behavior than a fixed ratio, a variable interval results in a steadier level of behavior than a fixed interval. Because students don't know when a quiz will occur, they are more likely to study every week rather than just before exams.

Gamifying Behavior Modification

Getting students to submit work on time in my online courses has always been a challenge. For many years while teaching online, I took points off for late work. This penalty was a negative punishment - I took something away (points) to lessen the likelihood of a behavior reoccurring (turning work in late). It is a common and rather traditional way to handle late work. Then, I took my MOOC journey, which included a course in Virtual Performance Assessment. In that course, we discussed the issue of handling late work, and one participant said something that flipped my thinking on its head.

"If you deduct points for work being late, you are grading them on their ability to follow the rules, not on learning the material."

He was right. Assigning A work a B grade just because it was late gives false feedback to the student. I had already been dissatisfied with the point deduction approach. For one thing, it always leads to pleas for extension, some of which are valid when you are dealing with adult learners with multiple responsibilities. For another, it didn't work very well.

So I stopped deducting points for late work and decided to gamify the submission of timely work. Now, instead of students losing points for late work, they earn a badge when they complete all of the work for a week, and if they earn that badge by the due date, they earn points - points and badges are game elements.

Giving them a badge and bonus points is a positive reinforcement, and reinforcement works better than punishment. Giving it on a weekly basis if they complete that week's work on time is a fixed interval reinforcement schedule, which means the reinforcement doesn't occur after every behavior, but after a fixed time period if the behavior occurred. To avoid the problem of a reinforcement losing its incentive over time, for every week in a row they get their work in on time, their bonus increases - half a point the first week, one point the second, one and a half the third, two the fourth, etc. If they miss a week, the next time they get the work done on time, the bonus starts over at a half a point. They still earn their badge, however, no matter when they get it done.

This approach has greatly increased on time work - and no one has to ask for an extension. As with any fixed interval, there is a flurry of activity right before the reinforcement is scheduled to occur, and most people do their work Sunday evening. For most assignments, that's OK. If they choose to do all of the work in one sitting (like a class that meets once a week), that's their choice.

However, each week they need to interact with their classmates in a blog or discussion, and waiting until the last minute to do that, is not conducive to the interaction I want to encourage, so I need to come up with a way to reinforce doing their blog or discussion early in the week. Maybe I'll try a negative reinforcement - the first student to do their blog doesn't have to comment on any other blog, and the student who posts second, has to respond to only one other blog. All other students would need to meet the assignment requirement of two comments. The problem with that, though is only a few students would benefit, when I want to get all students to complete the social activity early.

I'm going to try something that is done in the online courses I take from Adobe, the weekly winner. The rules for who gets the weekly winner award are never really defined, which is interesting. I earned this award three times (which, considering the sheer number of weeks of these classes I've taken, isn't surprising). Once was for the actual assignment I did, and another was for what I wrote about my assignment. This was the third, which I got for several reasons...including fessing up to watching Lethal Weapon instead of paying attention to the live online class, thus learning how important it was to pay attention in class. However, even the many times I didn't win influenced my behavior, because I looked at the work another winner did and tried to model that work in the future.

I'm going to try something that is done in the online courses I take from Adobe, the weekly winner. The rules for who gets the weekly winner award are never really defined, which is interesting. I earned this award three times (which, considering the sheer number of weeks of these classes I've taken, isn't surprising). Once was for the actual assignment I did, and another was for what I wrote about my assignment. This was the third, which I got for several reasons...including fessing up to watching Lethal Weapon instead of paying attention to the live online class, thus learning how important it was to pay attention in class. However, even the many times I didn't win influenced my behavior, because I looked at the work another winner did and tried to model that work in the future.

Since I can make up the rules for the weekly winner as I go, I can reinforce whatever I want. The first few weeks I will reinforce the behaviors on their social activities that encourage early but thoughtful submissions. Even though only one student can win each week, it can still reinforce behaviors in other students as they observe why the award was given. That's a concept called social learning, where seeing someone else's behavior being reinforced actually reinforces the behavior in the observer as well - and I'll talk about that more in the next blog.

So I stopped deducting points for late work and decided to gamify the submission of timely work. Now, instead of students losing points for late work, they earn a badge when they complete all of the work for a week, and if they earn that badge by the due date, they earn points - points and badges are game elements.

Giving them a badge and bonus points is a positive reinforcement, and reinforcement works better than punishment. Giving it on a weekly basis if they complete that week's work on time is a fixed interval reinforcement schedule, which means the reinforcement doesn't occur after every behavior, but after a fixed time period if the behavior occurred. To avoid the problem of a reinforcement losing its incentive over time, for every week in a row they get their work in on time, their bonus increases - half a point the first week, one point the second, one and a half the third, two the fourth, etc. If they miss a week, the next time they get the work done on time, the bonus starts over at a half a point. They still earn their badge, however, no matter when they get it done.

This approach has greatly increased on time work - and no one has to ask for an extension. As with any fixed interval, there is a flurry of activity right before the reinforcement is scheduled to occur, and most people do their work Sunday evening. For most assignments, that's OK. If they choose to do all of the work in one sitting (like a class that meets once a week), that's their choice.

However, each week they need to interact with their classmates in a blog or discussion, and waiting until the last minute to do that, is not conducive to the interaction I want to encourage, so I need to come up with a way to reinforce doing their blog or discussion early in the week. Maybe I'll try a negative reinforcement - the first student to do their blog doesn't have to comment on any other blog, and the student who posts second, has to respond to only one other blog. All other students would need to meet the assignment requirement of two comments. The problem with that, though is only a few students would benefit, when I want to get all students to complete the social activity early.

I'm going to try something that is done in the online courses I take from Adobe, the weekly winner. The rules for who gets the weekly winner award are never really defined, which is interesting. I earned this award three times (which, considering the sheer number of weeks of these classes I've taken, isn't surprising). Once was for the actual assignment I did, and another was for what I wrote about my assignment. This was the third, which I got for several reasons...including fessing up to watching Lethal Weapon instead of paying attention to the live online class, thus learning how important it was to pay attention in class. However, even the many times I didn't win influenced my behavior, because I looked at the work another winner did and tried to model that work in the future.

I'm going to try something that is done in the online courses I take from Adobe, the weekly winner. The rules for who gets the weekly winner award are never really defined, which is interesting. I earned this award three times (which, considering the sheer number of weeks of these classes I've taken, isn't surprising). Once was for the actual assignment I did, and another was for what I wrote about my assignment. This was the third, which I got for several reasons...including fessing up to watching Lethal Weapon instead of paying attention to the live online class, thus learning how important it was to pay attention in class. However, even the many times I didn't win influenced my behavior, because I looked at the work another winner did and tried to model that work in the future.Since I can make up the rules for the weekly winner as I go, I can reinforce whatever I want. The first few weeks I will reinforce the behaviors on their social activities that encourage early but thoughtful submissions. Even though only one student can win each week, it can still reinforce behaviors in other students as they observe why the award was given. That's a concept called social learning, where seeing someone else's behavior being reinforced actually reinforces the behavior in the observer as well - and I'll talk about that more in the next blog.